Costly Assumptions

16 Jan 2025

Drug discovery gone wrong: when linear thinking meets a folded genome.

In my previous post I spoke about how much of science was based on a molecular, particulate view of life — molecules that behave as molecules should — and how this subject was taught to several generations of molecular biologists for the past decades. And about how these assumptions are still dominant, and color the views and perceptions of the most lucrative and expansive life science industry there is today: biopharma.

Before I continue to point out where big pharma is operating on assumptions that we now know to no longer hold true, let me again take a short step back and extend some form of sympathy and understanding to this industry.

Every year the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) publishes a report on the state of the industry. According to last year’s annual report, the industry has been successful across many previously life-threatening indications. Take HIV/AIDS as an example. According to WHO and CDC numbers, deaths from HIV-related cases have come down by over 60% in the last decade in Europe. In 2023, 900,000 people were employed in the pharmaceutical industry, which generated product worth €390 billion.

Despite all the impressive successes, quoting this report, great challenges exist: “major hurdles remain, including Alzheimer’s, Multiple Sclerosis, many cancers, and rare diseases.” Their words, not mine.

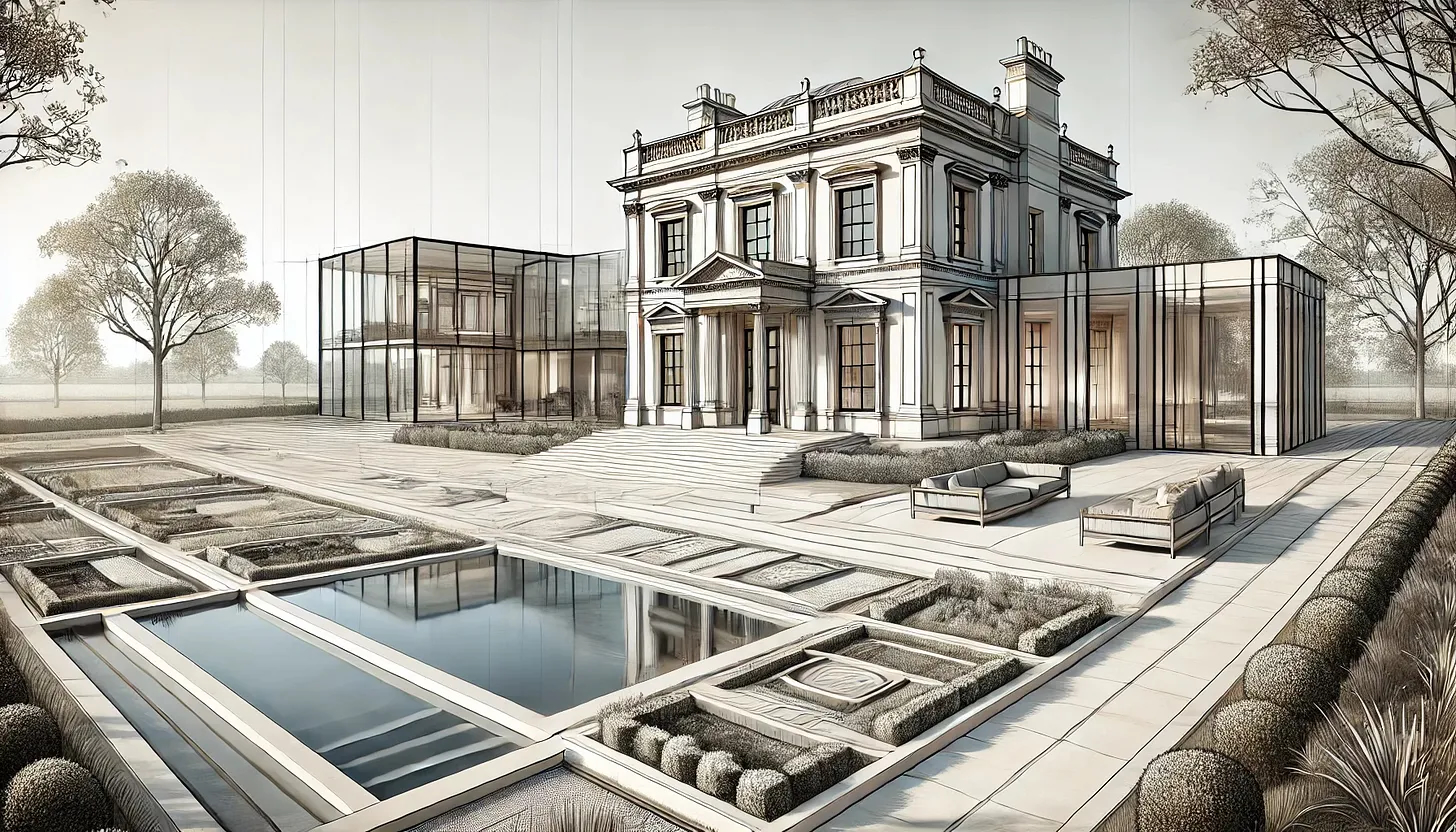

A few years ago, I was invited to a small and illustrious retreat organised by the Cambridge University School of Clinical Medicine. We met at the fabulous grounds of Chicheley Hall, now owned and maintained by the Royal Society. Our Institute had representatives present, as did the EBI (The European Bioinformatic Institute), and a few other schools or departments of the University. There was also a representative from one of the big four pharma companies present. Said company had recently relocated their headquarters to Cambridge at great expense. There were nibbles and wine, some networking conversations and of course the obligatory and more formal presentations. One stood out to me in particular: the representative from the global pharma company presented his work — or the work done in his department.

They had taken human genetic information, in the form of GWAS (or genome wide association studies), in order to find a druggable target for an as-yet untreated disease. I have since forgotten which disease. And, by the account of said individual — it seems he would like to have forgotten this whole saga, too. Let me explain why.

The human genome is an untidy beast. At last count, it contains about 3.2 billion base pairs — a number that is hard to visualise. Put another way, if you wanted to print out the entire human genome in book form, with each book containing 500 pages, you would need 3,200 books. Or, if held in bookshelves of normal height, about 21 bookshelves worth. For one genome, from one person. Complicating things: the books have no discernible order. No table of contents. No glossary, no index, nothing to help the inclined researcher make heads or tails of the overall content.

And even more infuriatingly still, the words — which in the language of the geneticists are the genes — are spread out irregularly, with pages of seemingly meaningless gibberish between them. The spacing between “sensible” words, or genes, is so vast that many statistics quote the genome to contain only 8–10% genes, with the rest being barely comprehensible sequences of letters that are thought to have little or no use or meaning at all. Little — but not none. The problem arises because a drug company can only generate a drug against a gene product — a word. There is as yet simply no way to target the “gibberish”. You have to identify the “word” that is causally linked to the disease.

This is the situation our friend from said large pharmaceutical company found himself in: they had managed to find an association between a genetic variant, a SNP, and the disease of interest. This alone is a significant accomplishment — doing enough sequencing and annotation to find a signal at all is a huge feat. Hundreds of papers describe such associations as a result in and of themselves.

This is where things get messy: most of the time the identified genetic variation is in the “meaningless” region between genes. That is, most disease-associated variants are located at what is known as “intergenic regions” — DNA sequences at great distances from any sensible word, or druggable target gene. This is like being given an invitation to a very swanky dinner party in the best part of town, but the address shown is that of a distant public parking space. You have no idea to which house you should go.

Luckily, DNA is linear — literally a single thread of information, unlike the 2-dimensional area of a city map. So what most researchers do, when they have found a genetic variant that is located in this “intergenic” region, is that they look a few genes to the left and a few genes to the right and pick the one that looks most promising. The invitation might have clues: such as “join us for a poolside party with a great view over the valley…”. You can then gatecrash the nearest house that more or less matches that description in the hope that the residents are expecting you.

This is more or less what the company did. They found a roughly matching location — a gene, not a house — and started to develop a drug against it.

This is no small endeavour. Any drug company will proudly present you with the inordinate costs associated with getting a drug to market. The current going rate is anywhere between 500 million US$ to over 2 billion. This is for one drug to make it through all stages of development, testing, and clinical trials.

The drug our presenter was developing never made it that far. After two years of intense work, and after having spent roughly £80 million, they had figured out that they were at the wrong address. They had knocked, rung the bell, looked over the fence and seen tantalising clues — a pool maybe and a terrace overlooking the valley — they had dressed up and brought bubbly, some flowers and felt excited for the evening. But alas, there was no party and they were bluntly turned away. Their assumptions turned out to have been based on faulty logic: the DNA molecule may only be linear, but inside the cell it is not stretched out into a single long filament. Rather, and once again things get complicated and seemingly disorganised, DNA is packed into arcane 3D shapes: it folds and runs in loops, clusters of loops and clusters of clusters. More Inception than Manhattan. It has now been shown that these genomic structures are in fact functional and highly organised: sequences that are very distant in linear sequence can actually be close neighbours in 3D space. Not only can they be — they have to be, for things to work properly in a gene regulatory context. Even back then this was established knowledge among leading scientists.

What the company had simply failed to do was take this knowledge into account. They based their identification of the target gene on the assumption that 3D organisation of the genome didn’t matter. This clearly showed once more that not listening to the leading edge of science is a very costly mistake to make.